The Odyssey: An Epic That Shaped Western Storytelling

Homer’s The Odyssey isn’t just an ancient story—it’s the blueprint for Western literature. Written in the 8th century BCE and set in a mythic version of Greece, this epic poem weaves together history, mythology, and cultural values to explore homecoming, identity, and survival. As The Odyssey enjoys renewed attention thanks to projects like Epic: The Musical and Christopher Nolan’s upcoming adaptation (2026), it’s worth revisiting the original story and why it continues to shape how we tell stories today.

Homer’s The Odyssey isn’t just an ancient story—it’s the blueprint for Western literature. Written in the 8th century BCE and set in a mythic version of Greece, this epic poem weaves together history, mythology, and cultural values to explore homecoming, identity, and survival. As The Odyssey enjoys renewed attention thanks to projects like Epic: The Musical and Christopher Nolan’s upcoming adaptation, it’s worth revisiting the original story and why it continues to shape how we tell stories today.

The World Behind The Odyssey

The Odyssey—one of the most enduring works in Western literature—was composed in the late 8th century BCE, during a transformative period in ancient Greek history. But it wasn’t written in ink. It was sung. Performed aloud by traveling poets known as rhapsodes, who memorized thousands of lines and recited them at festivals, courts, and gatherings. These oral poets didn’t just repeat a fixed script—they adapted the tale for different audiences, drawing on a deep tradition of formulaic storytelling. What we read today is likely the crystallized version of a much older, evolving song that had been shaped over generations.

This was the tail end of the Greek Dark Ages—a time with no widespread writing system, after the fall of the Mycenaean palaces around 1200 BCE. For centuries, the Greeks passed down stories through speech alone. The eventual invention of the Greek alphabet (adapted from the Phoenicians) allowed these epics—The Iliad and The Odyssey—to be written down, probably for the first time in the 6th century BCE. But by then, they were already ancient in the eyes of the people who told them.

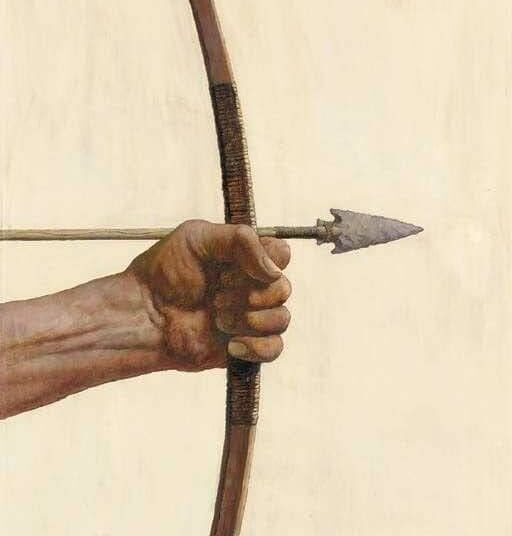

The Odyssey looks back on a mythic Bronze Age, framed around the Trojan War. Long believed to be pure fiction, that war now appears to have a possible historical basis. Archaeologists have uncovered ruins at Hisarlik in modern-day Turkey, widely considered the site of ancient Troy. Layers of destruction suggest that a major conflict may have occurred there around the time Greek oral tradition places the war. Still, The Odyssey is not a factual account—it’s a product of cultural memory. It reveals how the Greeks wanted to imagine their heroic past: a world of honor, adventure, divine intervention, and hard-won homecomings.

Odysseus himself probably never existed, at least not as a single real person. But he embodies the qualities that the Greeks saw as heroic: cleverness, adaptability, endurance, and eloquence. Unlike Achilles, the idealized warrior of The Iliad, Odysseus is a survivor. He lies, tricks, negotiates, and hides. He doesn’t win glory in battle—he earns his legacy through resilience and cunning. In many ways, he reflects a cultural shift from brute force to strategic intelligence, a trait that resonated with a more democratic, seafaring, and competitive Greek society emerging in the archaic period.

The world of The Odyssey straddles fact and fantasy. Some locations, like Ithaca and Pylos, were real Greek kingdoms. Others—the land of the Lotus-Eaters, the Cyclops’s island, the Underworld—belong to the symbolic realm. These invented geographies serve as psychological and moral landscapes. They challenge Odysseus not just physically, but emotionally and spiritually. Each place represents a trial: forgetfulness, pride, temptation, grief, or fear of death.

Perhaps most telling is how The Odyssey reflects Greek values. Hospitality (xenia) wasn’t optional—it was a sacred duty tied to Zeus himself. Welcoming strangers, offering food and gifts, and honoring one’s guests were moral obligations. Violating xenia could bring disaster, as it does for the suitors who overrun Odysseus’s home. Respect for the gods, loyalty to family, and perseverance in the face of overwhelming odds weren’t just themes—they were virtues that shaped daily life and political ideals in ancient Greece.

And running beneath it all is the presence of the divine. The gods in The Odyssey are not distant figures—they are intimately involved in human affairs. Athena mentors and protects. Poseidon punishes. Hermes delivers messages. The ancient Greeks believed fate and free will were locked in a constant tug-of-war, with the gods steering outcomes but never fully determining them. Mortals still had choices—and those choices had consequences.

Even the way the poem is structured offers cultural insight. The Odyssey is rich with repeated phrases, epithets, and set scenes—hallmarks of oral-formulaic composition. These weren’t signs of creative laziness. They were tools for memory, rhythm, and performance. They allowed rhapsodes to tell a story that could stretch over days while keeping the audience engaged, even comforted, by familiar patterns and language.

So no—The Odyssey isn’t a historical document. But it is a mirror. It reflects how ancient Greeks thought about their world, their place in it, and what it meant to survive it. It’s part myth, part memory, and completely essential if you want to understand the roots of storytelling in the West—and the values that helped define a civilization.

Structure and Plot of The Odyssey

If you’re expecting The Odyssey to start at the beginning—think again. Like many epics that would follow in its footsteps, The Odyssey begins in medias res—right in the thick of things. Odysseus had been missing for nearly 20 years. The Trojan War is long over, but he hasn’t made it home, and back in Ithaca, his kingdom is unraveling. This choice to start in the middle isn’t just a storytelling flourish—it’s a hallmark of oral epic tradition, where the audience already knows the broad strokes. What matters is how the tale is told and what new layers of meaning emerge in the retelling.

The poem opens not with Odysseus, but with his son, Telemachus—a young man on the cusp of adulthood, growing up in his father’s shadow but without his guidance. His palace is overrun by suitors: arrogant, entitled nobles feasting on his inheritance and pressuring his mother, Penelope, to remarry. Telemachus lacks the power to challenge them and the wisdom to know what to do next. He barely remembers his father at all.

Enter Athena. As Odysseus’s divine protector, she sees that the moment is ripe for action. Disguised as the family friend Mentes, she urges Telemachus to seek answers: visit the surviving heroes of the Trojan War and find out if his father still lives. What follows is often called the “Telemachy”—the first four books of The Odyssey—in which the son embarks on his own journey of discovery. He meets Nestor in Pylos and Menelaus in Sparta, and though he learns little about Odysseus’s fate, the trip changes him. He begins to claim his lineage, stepping into a more confident, active role—essential groundwork for the reunion and reckoning still to come.

Only in Book 5 do we meet Odysseus himself. And he’s not battling monsters—he’s weeping on a beach. Trapped for seven years on the island of Ogygia, held by the nymph Calypso, he’s been offered immortality and divine love if he stays. But he refuses. His heart is still with Ithaca. He would rather grow old—and die—as a mortal man than live forever without his home and family. The gods intervene. Hermes arrives with Zeus’s command, and Calypso, heartbroken, agrees to let him go. Odysseus builds a raft and sets out, only to be immediately wrecked by Poseidon, still seething over past offenses. Battered and alone, he washes ashore in the land of the Phaeacians.

Here, the narrative structure shifts again. Welcomed as a stranger, Odysseus remains anonymous until he begins to tell his tale—and The Odyssey becomes a story within a story. Over four books, he recounts his harrowing journey from Troy to Calypso’s island. These episodes are not just adventures—they are moral tests and emotional scars. And each one deepens our understanding of his character.

- The Cicones: Fresh from victory, Odysseus and his men raid a Thracian city. But they stay too long, and reinforcements arrive. Many are killed. It’s a lesson in overconfidence—and the first hint of the cost of delay.

- The Lotus-Eaters: A gentle but dangerous people offer food that makes men forget home. Odysseus must drag his crew away, reminding them—and himself—of what’s at stake.

- The Cyclops: The most famous episode. A stop for supplies turns into a deadly trap inside Polyphemus’s cave. Odysseus’s cleverness—blinding the Cyclops and escaping under sheep—saves them. But his ego undoes him. He shouts his name as they flee, prompting Polyphemus to pray to Poseidon for revenge.

- Aeolus: The wind god gifts Odysseus a bag of winds to carry him home. Ithaca is within sight. But his curious, distrustful crew opens the bag, thinking it’s treasure. The winds scatter them back across the sea.

- The Laestrygonians: Giant cannibals who destroy every ship but Odysseus’s. The fleet is gone. The body count rises.

- Circe: A powerful sorceress who turns men into pigs. With Hermes’s help, Odysseus resists her spell and becomes her lover. They stay a full year, resting and recovering. It’s a detour, but also a reminder: time, too, can be a monster.

From Circe’s island, Odysseus is told to descend into the Underworld—a rare, chilling journey for a living man. There, he speaks to the prophet Tiresias, who warns him not to touch the cattle of the sun god Helios. He also sees his mother, who died from grief in his absence, and fallen comrades from the war. This moment breaks open the emotional core of the epic. It’s not just about clever tricks or divine help—it’s about loss, regret, and the high cost of survival.

From there, his path grows darker:

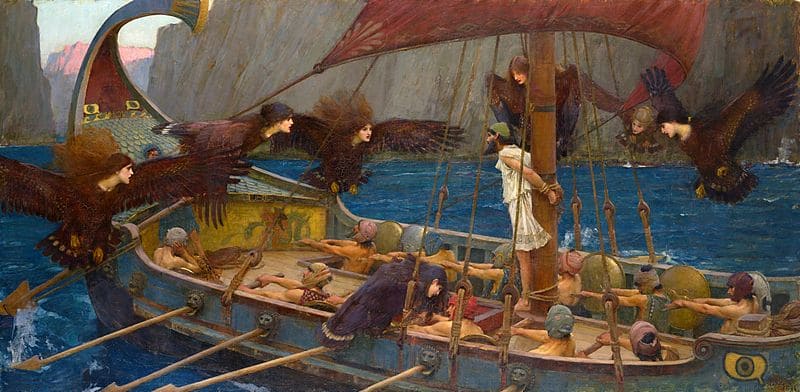

- The Sirens: Their irresistible song draws sailors to ruin. Odysseus, curious but cautious, plugs his crew’s ears and has himself tied to the mast so he can listen safely. It’s one of the most haunting metaphors in the poem: the struggle to resist what you most desire.

- Scylla and Charybdis: A literal rock-and-hard-place. He loses six men to the six-headed Scylla while trying to avoid Charybdis’s whirlpool. The price of passage is always blood.

- Thrinacia (Helios’s island): Despite warnings, his starving crew slaughters the sacred cattle. The gods respond with fury. Zeus sends a storm. The ship is destroyed. Everyone dies—except Odysseus.

He drifts alone to Calypso’s island, and the timeline catches up. His story, and the story of The Odyssey, is finally ready to resume.

Moved by his suffering and skill as a storyteller, the Phaeacians ferry him home. But Ithaca is no longer safe. Odysseus returns not as a conquering hero but as a beggar in disguise. He hides, watches, and plans. Athena helps orchestrate the reunion with Telemachus, and together they scheme to reclaim the palace.

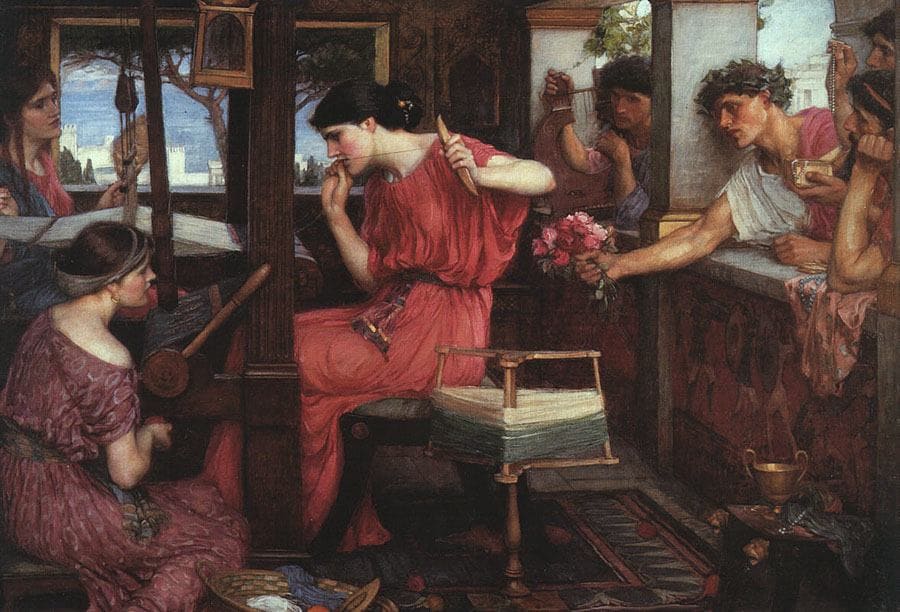

Inside, Penelope is playing her own game—faithfully resisting the suitors for years by weaving and unweaving a shroud. But the ruse is nearly up. She announces a contest: whoever can string Odysseus’s great bow and shoot an arrow through twelve axe heads will win her hand. No one succeeds. Until the beggar steps forward.

With calm precision, Odysseus strings the bow and fires. One shot. Perfect aim. In that moment, he reveals himself—and unleashes vengeance. The suitors are slaughtered. It’s brutal, bloody, and complete.

And yet, the climax isn’t over. Penelope, cautious after so many years of waiting and deceit, tests him one last time. She tells a servant to move their bed—knowing it can’t be moved because Odysseus built it himself from the trunk of a living olive tree. When he reacts with outrage, she knows it’s truly him.

The final book is one of restoration. The families of the suitors demand justice. Civil war looms. But Athena steps in, enforcing peace. Harmony, at last, is restored.

So yes, The Odyssey is about monsters, gods, and impossible odds. But it’s also about homecoming, identity, and what it takes to reclaim the life you left behind. Odysseus doesn’t just return—he has to rebuild his place in a world that moved on without him. That journey, full of loss, resilience, and rediscovery, is what makes The Odyssey not just a myth—but a masterpiece of human storytelling.

Why The Odyssey Still Speaks to Us

Even though The Odyssey is over 2,500 years old, it doesn’t feel like a dusty relic. It’s not a museum piece—it’s a living, breathing narrative that still resonates because it doesn’t pretend to be a perfect story with perfect people. It’s a long, painful, and often messy return home. It’s about a man who loses everything—his ships, his crew, his reputation, his humanity—and has to claw his way back, piece by piece, not just to a place, but to a version of himself he can live with.

At its core, The Odyssey is a story about recovery. About surviving the aftermath. About navigating the wreckage of war, trauma, time, and pride—and somehow still wanting to rebuild. That’s why it endures. It’s not just about travel and monsters—it’s about memory, survival, and the fragile, unfinished self that’s waiting at the end of the road.

And while many of its themes are front and center, others linger quietly in the shadows, surfacing through contradictions, choices, and character flaws. Together, they give the epic its staying power.

Identity and Reinvention

Odysseus is constantly changing, both physically and mentally. Throughout the poem, he takes on disguise after disguise—beggar, stranger, war hero returned from the dead. He lies constantly, not just to others but arguably to himself. Not because he’s dishonest, but because survival demands it. The war stripped away his former self, and the journey home keeps reshaping him. Is he the ruthless strategist who left Troy? The heartbroken man on Calypso’s island? The cold avenger in Ithaca? He’s all of them—and none of them. The poem never lands on a fixed answer. Maybe that’s the point. Identity, The Odyssey suggests, isn’t static. It’s forged through experience, adaptation, and the hard choices we make along the way.

Loyalty and Testing

Penelope has become an icon of loyalty—cleverly holding off the suitors for two decades, weaving and unweaving a shroud to buy time. But what’s less often noted is that Odysseus doesn’t immediately trust her in return. When he finally comes home, he doesn’t walk into her arms. He watches. Tests. Waits. Just as she has remained vigilant, so does he. Loyalty in The Odyssey isn’t assumed—it’s proven. And the emotional weight of the story rests in this mutual testing: the quiet, painful need to be sure, after so many years of betrayal and uncertainty.

Temptation and Discipline

Nearly every stop on Odysseus’s journey offers him a chance to give up. The Lotus Eaters offer oblivion. Circe offers pleasure. Calypso offers immortality. And for a while, he accepts some of these gifts. He stays too long. He loses time. But in the end, he always chooses the hard road forward. Not because he’s immune to temptation—but because he learns to resist it. That struggle between desire and duty, comfort and calling, is what makes him feel so human. He doesn’t always get it right. But he keeps going.

Cunning Over Strength

Where The Iliad glorifies Achilles’s rage and physical might, The Odyssey champions something else entirely: cunning. Odysseus wins with his brain, not his sword. He deceives the Cyclops, tricks Circe, and outsmarts the suitors. His intelligence is his superpower—but it’s also his weakness. His cleverness saves him, but it also makes him arrogant, manipulative, and deeply secretive. He survives not because he’s the strongest but because he’s the most adaptable—and because he knows when to play the long game.

Fate vs. Free Will

The gods are everywhere in The Odyssey. They send omens, alter winds, wand hisper in dreams. But they don’t control everything. The epic strikes a delicate balance between divine influence and personal agency. Odysseus is certainly guided—by Athena’s protection, by Zeus’s decrees—but he still has to make choices. And those choices matter. His victories often come from insight. His suffering, more often than not, comes from his own impulsiveness. Fate may set the stage, but free will writes the dialogue.

Hubris and Consequence

Odysseus is brilliant—but he’s also proud. And that pride, or hubris, nearly ruins him. After blinding the Cyclops, he can’t resist taunting him and shouting his name. That moment of vanity is what dooms him. Poseidon hears Polyphemus’s prayer and ensures Odysseus’s journey drags on for years. This isn’t just a plot twist—it’s a recurring lesson in Greek literature: pride brings downfall. And even heroes, especially heroes, must learn the cost of letting their egos speak louder than their wisdom.

That’s part of what makes The Odyssey so rich, and so human. It doesn’t offer tidy lessons or moral blueprints. It doesn’t say, “Here’s how to be a hero.” Instead, it shows us a deeply complicated man navigating grief, guilt, temptation, and loss—often failing, sometimes succeeding, and always moving forward.

The story isn’t just about how to win. It’s about how to return. And how to live with the scars.

That kind of story never really goes out of style.

The Literary Legacy of The Odyssey

Long before we had a name for the “hero’s journey,” The Odyssey gave us the blueprint: a reluctant departure from home, a long arc of trials and transformation, and a hard-won return. That structure has echoed across millennia, shaping narratives from ancient epics like The Aeneid to modern sagas like The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, and beyond. Joseph Campbell’s monomyth—the storytelling framework taught in film schools and writing classes—traces its roots directly to Odysseus’s path.

But what endures isn’t just the structure. It’s the emotional depth underneath it.

Each generation finds its own version of The Odyssey. Jorge Rivera-Herrans’s Epic: The Musical reframes the tale through song and vulnerability, centering Odysseus’s internal struggles—grief, guilt, trauma—just as much as his outer trials. It’s a retelling that speaks to a generation for whom heroism looks more like survival than conquest. Christopher Nolan’s upcoming film adaptation, meanwhile, promises to explore the psychological fallout of war, memory, and identity—what it feels like to come home a stranger to yourself.

These aren’t just modern updates. They’re reminders that The Odyssey is still very much alive. We don’t keep revisiting it because it’s ancient—we revisit it because it still fits.

At its heart, The Odyssey isn’t just the story of a man trying to get home. It’s about everything he loses on the way there. Everything he carries with him. And everything he has to become to find his way back. It’s not just a myth—it’s a mirror. And whether we’re lost at sea or just navigating the chaos of modern life, we’re all on some version of that journey.

Want To Learn More?

If you’re ready to dive deeper into Homer’s epic, you can read or download The Odyssey online. For historical context, the British Museum offers an excellent overview of the myth’s origins and relevant artifacts. You can also read more on Christopher Nolan’s new adaptation of The Odyssey coming in 2026.