The Potato Eaters

Above them, the lamp bleeds—

a ruptured eye

weeping thick yolk

that spatters across warped wood,

everything beneath it

made uglier by its gaze.

Potatoes slump in their skins,

steam coughing out from each torn belly.

They stink of soil,

like something clawed too early from the grave.

No salt. No lard. No mercy.

Just flesh gone soft enough to swallow

without chewing too long.

A child breathes through his teeth—

the sound is sharp, rodent-like.

He eats with both hands,

nails rimmed black with field rot.

The hunger is older than him.

He was born gnawing.

Born already buried

to the wrists in cold earth.

The man at the head grips a cup

like it might vanish—

his fingers curled, cracked,

thumb blistered from the plow handle’s bite.

He drinks scalding brew without blinking.

If it burns, it proves

he’s still a body.

The mother’s eyes are not eyes—

just sockets sunk behind soot and skin,

shadows eating shadows.

She counts bites in her mind,

rations prayers between molars,

licks grease from the creases of her palm

as if it were wine.

A cough cracks the silence—

wet, with something coming loose.

Maybe a lung.

Maybe a memory

of a harvest with color.

Outside, frost fists the glass,

its breath a warning.

Inside, mouths move like machinery

long past rust,

grinding down the root

until there’s nothing left

but tongue and want.

They sit in their sweat,

in their breath,

in the steam rising from what little

was dragged from the ground today.

There’s dirt on the table,

in the lines of their faces,

under their tongues.

They cannot tell

where it ends

and they begin.

Each swallow is a prayer,

each prayer

a failure

they chew anyway.

Even the dog in the corner

stares with ribs like roof beams,

waiting for peelings,

for ash,

for God.

The lamp’s hiss is the only god here,

spitting its judgment

on meatless fingers

and the small salvation

of one more bite.

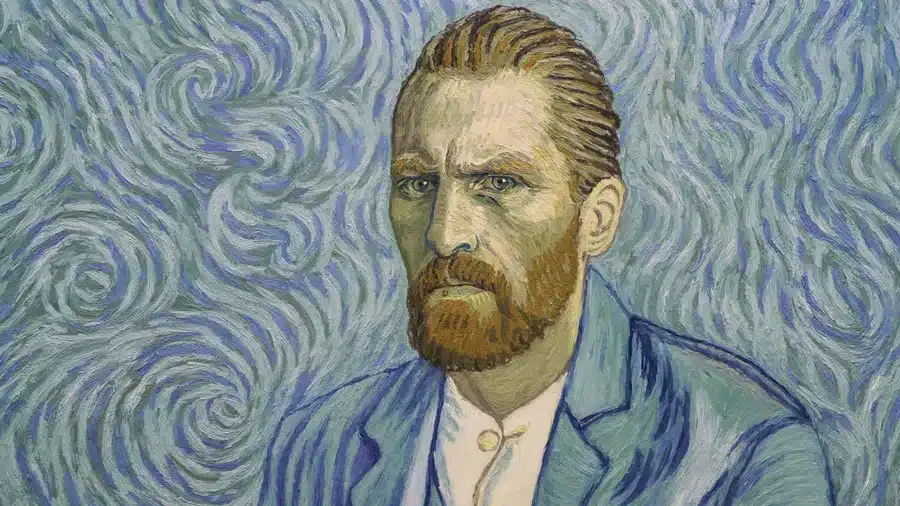

About The Potato Eaters by Vincent van Gogh

When Van Gogh painted The Potato Eaters in 1885, he was pushing back against a popular trend in art: turning peasant life into something soft and sentimental. A lot of artists at the time made rural poverty look almost charming—rosy cheeks, golden sunsets, that kind of thing. Van Gogh wasn’t interested in that. He wanted to show the real thing. The hard thing. The people in his painting are tired, their faces are worn, the light is dim and unforgiving. It’s not pretty—but that was the point.

He wrote The Potato Eaters to his brother Theo saying he meant for it to look rough. These weren’t models posing as peasants—they were actual workers, living off what they pulled from the ground. Van Gogh saw something deeply human in that kind of life, and he didn’t want to clean it up for the sake of art. If anything, The Potato Eaters is his way of saying: this is what survival looks like. Messy. Raw. Real.

And in that, there is a kind of dignity that doesn’t need to be dressed up. Not the polished, storybook kind, but the kind that comes from endurance. From scraping together a meal with dirt still under your nails. Van Gogh wasn’t trying to make you feel comfortable with The Potato Eaters—he was trying to make you feel something. The hunger, the cold, the closeness, the grind of daily life. The Potato Eaters isn’t about suffering for sympathy—it’s about recognizing the quiet strength it takes just to keep going.