The Physics of Baseball was written in 1994 by Robert Adair. The Physics of Baseball is a short book, only 142 pages, but it has lots of figures to illustrate the principles of baseball. The Physics of Baseball has chapters on the flight of the baseball, pitching, Running, Fielding, and Throwing; Batting; and the properties of bats.

There are 38 figures used to illustrate the many equations in the book. In The Physics of Baseball Adair investigates both practice concepts, such as how to throw a particular kind of pitch, and historical topics like the plausible trajectory of a home run hit by Mickey Mantle. Do you believe you can learn from this book?

How to Throw a Knuckleball

The Physics of Baseball has a great explanation in it of how to throw a knuckleball. Basically, the airflow over the stitches of the ball causes it to curve. So, a ball thrown with no spin, which is how one throws a knuckleball, is not curved by disruptive airflow. In this case, asymmetric stitch configurations can be generated by the pitcher which leads to large imbalances of forces and wild changes in pitch trajectory.

This area of discussion, by the way, on page 31 includes how to rotate four other pitches. A fastball, curveball, slider, and screwball. In fact, there is a helpful diagram. A diagram that proves the adage that a slider is just a failed curveball. Adair notes that he did simulations in a wind tunnel to prove these assertions.

Left-Handed Hitters Vs. Right-Handed Hitters

To give the reader a further idea about what kind of data is in The Physics of Baseball, Adair has a table in Figure 5.2 that is instructive. In that figure, Adair examines all of the at-bats in major league baseball between 1984 and 1987. There were 101,714 at-bats in baseball during that time. What Adair is interested in is whether, late in the game, it makes sense to insert a right-handed batter against a left-handed pitcher, and vice-versa.

Adair analyzes the data and concludes, “For the average batter and average pitcher. changing pitchers (or batters) to take advantage of the left-right match is worth .0287 for left-handed hitters and.0164 for right-handed batters.” So, there is an advantage to batting from the opposite side of a pitcher. Adair concludes that this is because batters who bat from the opposite side as the pitcher see curveballs more clearly.

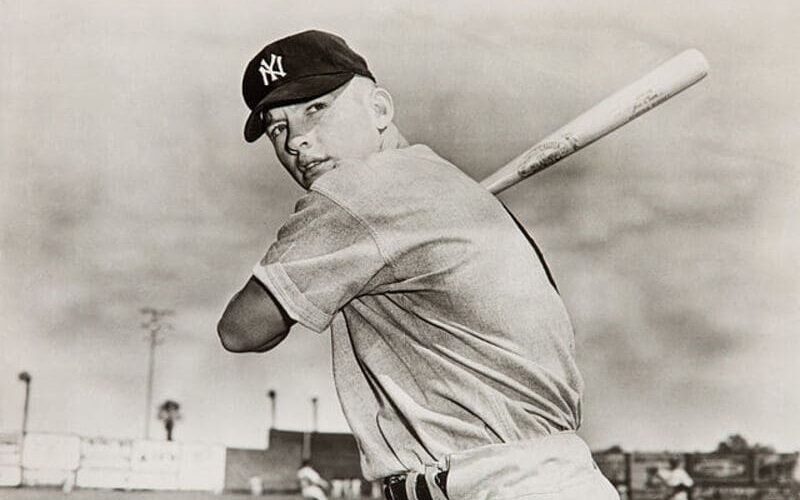

The Flight of a Home Run by Mickey Mantle

The most famous home run Mickey Mantle ever hit was a 565-foot moonshot at Griffeth Stadium in Washington DC off Chuck Stobbs in 1953. Adair estimates in The Physics of Baseball that the Mantle home run was wind-aided and traveled only 506 feet. He says that at sea level and in calm conditions a batter would need a bat speed of 76 miles per hour to hit an 85-mile-per-hour fastball 400 feet to center field. To hit the ball 450 feet, the batter would need to generate 86 miles per hour of bat speed. That is a 13% increase. To hit the ball 500 feet, you would need 50% more energy.

The Physics of Baseball’s Verdict

The Physics of Baseball is a very good book to read if you want to understand what is happening in a baseball game. The discussion is straightforward, and the illustrations (as figures) help a great deal. It is also helpful that Adair did experiments to back up his points. All baseball fans will want to read this book, there is even a discussion of corked bats. However, be warned, there are a lot of equations in The Physics of Baseball.