Why Montgomery’s Civil Rights Trail Is One of February’s Most Powerful Trips

A trip to Montgomery’s Civil Rights Trail is a trip that sits with you long after you’ve unpacked your suitcase. One that shifts something in you. Montgomery, Alabama, is one of those places, especially in February. With Black History Month in full swing, the city feels like it’s holding its breath and telling its story at the same time.

Montgomery doesn’t try to soften its history. It doesn’t wrap it in pretty packaging or pretend the hard parts didn’t happen. Instead, it invites you to walk straight into the truth and the good, the painful, the resilient, the triumphant. We see how it shaped the country we live in now. This isn’t a lighthearted getaway. It’s a meaningful one.

The Legacy Museum: A Gut‑Punch in the Best Way

If you only have time for one stop, make it the Legacy Museum. It’s not the kind of museum where you stroll through casually. It’s immersive, emotional, and incredibly well‑designed. You move from the history of enslavement to the era of racial terror, to segregation, to mass incarceration and the transitions hit hard.

The exhibits don’t sensationalize anything. They don’t need to. The truth is powerful enough on its own. You’ll see people standing quietly, taking their time, wiping their eyes. Nobody rushes through this place. You can’t.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice: Quiet, Heavy, Necessary

A short drive away is the memorial. An outdoor space dedicated to the victims of racial‑terror lynchings. It’s peaceful, but not in a comforting way. More like a “you need to stand here and feel this” way.

Rows of steel monuments hang from the ceiling, each one representing a county where lynchings occurred. Names are etched into the metal. Thousands of them. Some you recognize from history books. Most you don’t. Walking through the memorial in February, when the air is cool and the crowds are respectful, feels different. It feels intentional. Like the city is saying, “Remember this. Don’t look away.”

Historical Context That Grounds the Journey

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice documents more than 4,400 racial‑terror lynchings across the United States between 1877 and 1950. Alabama accounts for more than 360 of them. Montgomery County’s column includes victims such as Jim Pressley (1889), John Temple (1894), William Powell (1895), and George Meadows (1899). Their deaths were carried out by mobs, often in public, without consequence.

Alabama’s historical record also includes cases where perpetrators were named but never held accountable. In 1944, the kidnapping and assault of Recy Taylor in Abbeville resulted in no indictments, despite confessions from Hugo Wilson, Dewey Livingston, and Herbert Lovett. A grand jury refused to charge them. Their names remain part of the documented record because the legal system declined to act.

Montgomery’s Civil Rights Trail intersects with the people who reshaped the nation’s conscience. Rosa Parks was arrested here on December 1, 1955, for refusing to surrender her bus seat. E.D. Nixon, a longtime organizer and Pullman porter, coordinated her legal support and helped launch the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Jo Ann Robinson, of the Women’s Political Council, mimeographed tens of thousands of leaflets overnight to mobilize the city.

From his home on South Jackson Street, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led the 381‑day boycott that challenged the city’s segregated transit system. His house was bombed in January 1956 while his wife and infant daughter were inside. King continued to organize from that same home, hosting strategy meetings, writing speeches, and coordinating carpools that kept the boycott alive until the Supreme Court ruled bus segregation unconstitutional.

Nine months before Parks, Claudette Colvin, at age 15, refused to give up her seat and was arrested. She later became one of the plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle, the case that ultimately ended bus segregation in Montgomery.

These names, places, and events are not abstractions. They are the documented history of what happened on these streets and in these courtrooms, churches, and neighborhoods.

“The Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 | Black American Heroes | History” via HISTORY /YouTube

Walking the Streets Where History Happened

Montgomery isn’t a place where history is tucked away in museums. It’s right there in the streets. You can stand at the bus stop where Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat. You can walk past the church where Dr. King preached. You can follow the path of the Selma‑to‑Montgomery march.

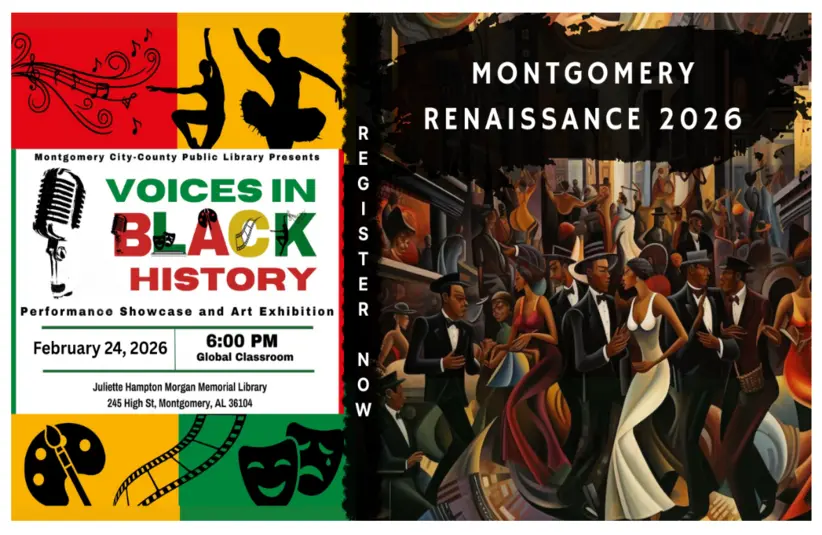

Nothing is overly polished. Nothing feels staged. The city lets the history speak for itself. And in February, when schools, churches, and community groups are hosting events, lectures, and tours, the whole place feels alive with remembrance.

The Practical Stuff (Because Every Trip Has Logistics)

Montgomery is easy to navigate, but some sites get crowded during Black History Month. Weekdays are calmer. Parking can be hit‑or‑miss near the major museums, so give yourself extra time.

Food options near the historical district are limited, but a short drive opens up plenty of local spots, including several Black‑owned restaurants that are absolutely worth your time. Hotels fill up faster in February, so booking ahead is smart.

Head South, Learn A Lot

Montgomery isn’t just going to be a “fun” trip, but it’s one of the most important ones you can take, especially in February. It’s a place that asks you to slow down, pay attention, and sit with the weight of history. And somehow, in the middle of all that heaviness, there’s also hope. You see it in the people, the art, the memorials, the way the city honors its past without being defined by it.

If you’re looking for a February trip that means something, something real, Montgomery delivers. You can walk the path of a history with more duality than any society should ever have to live through and remember how far we’ve come. You can stand in the places where ordinary people demanded extraordinary change and feel grateful that our children grow up in a world shaped by that courage.

And then, as you leave, you may notice how familiar some of the stories still feel and realize that history doesn’t stay in the past just because we wish it would.