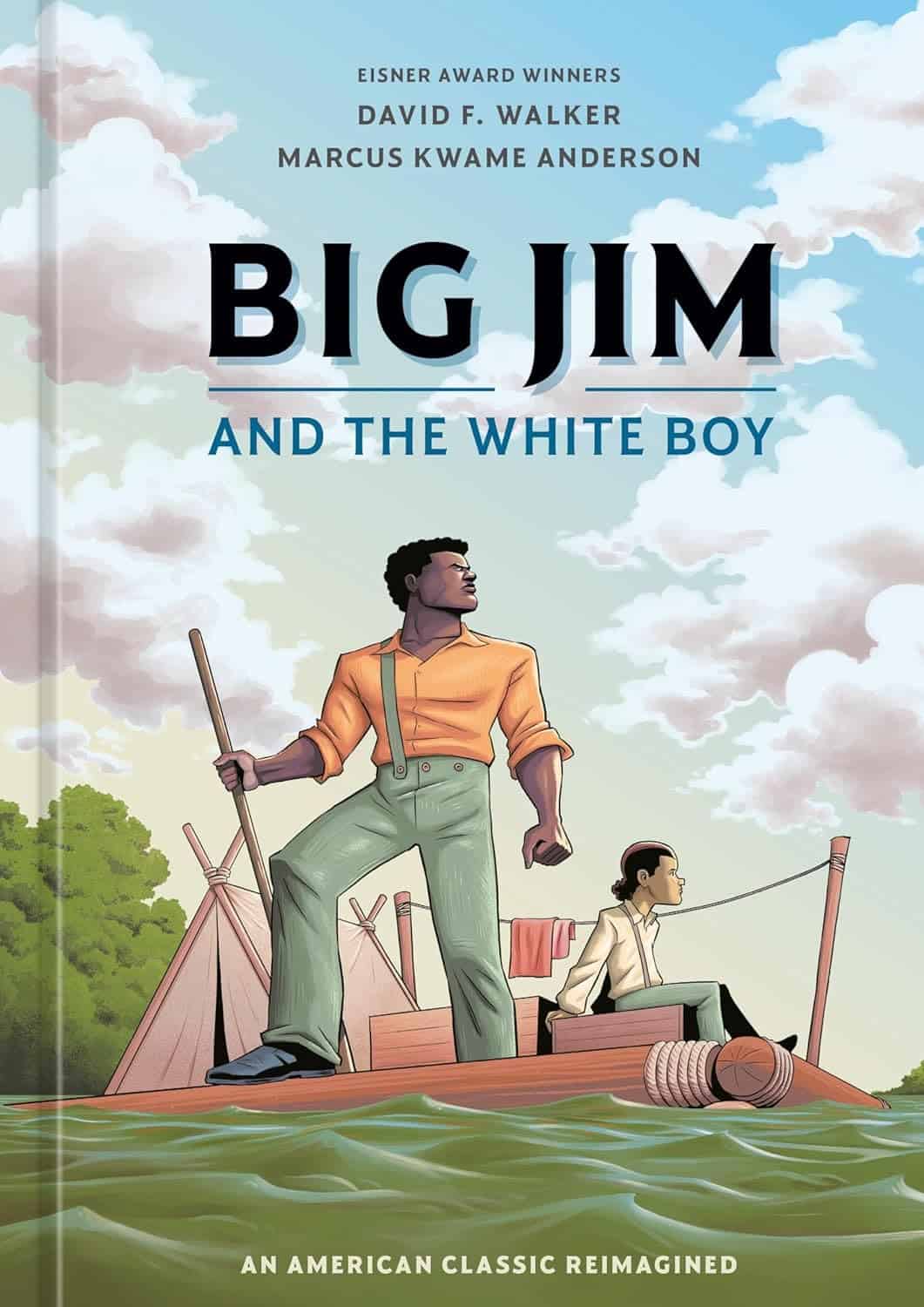

Big Jim and the White Boy: A Graphic Novel That Rewrites the Rules of American Literature

Big Jim and the White Boy isn’t just a reimagining of Mark Twain’s classic—it’s a reclamation. Writer David F. Walker and illustrator Marcus Kwame Anderson don’t tiptoe around the legacy of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. They confront it head-on, by writing a graphic novel that centers agency, humanity, and historical truth. The result is a layered, emotionally intelligent work that speaks to both the past and the present.

Rethinking Huck Finn: Why Big Jim Deserves the Spotlight

For generations, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been hailed as a cornerstone of American literature. But reverence alone doesn’t excuse its blind spots. Jim—arguably the novel’s most complex character—has long been kept to the margins. His story was filtered through the lens of antebellum stereotypes.

Big Jim and the White Boy changes that. Walker asks the question that’s lingered for over a century: What if Jim’s was center stage?

Rather than avoiding the discomfort that’s a part of Twain’s original, Walker leans into it. His approach is bold and restorative, preserving the essence of Huck and Jim’s journey while dismantling the structures that silenced Jim. At San Diego Comic-Con 2025, Walker shared, “This isn’t just a retelling. It’s choosing to treat Jim as more than a character who exists to serve Huck’s story. It’s about giving him depth, autonomy, and a voice.”

Big Jim and the White Boy: A Story Told Through Memory and Meaning

Walker’s narrative device, a reflective framing set in the 1920s, adds emotional weight and historical context. An elderly Jim and Huck, surrounded by grandchildren, look back on their journey down the Mississippi. This choice humanizes them, transforming myth into memory.

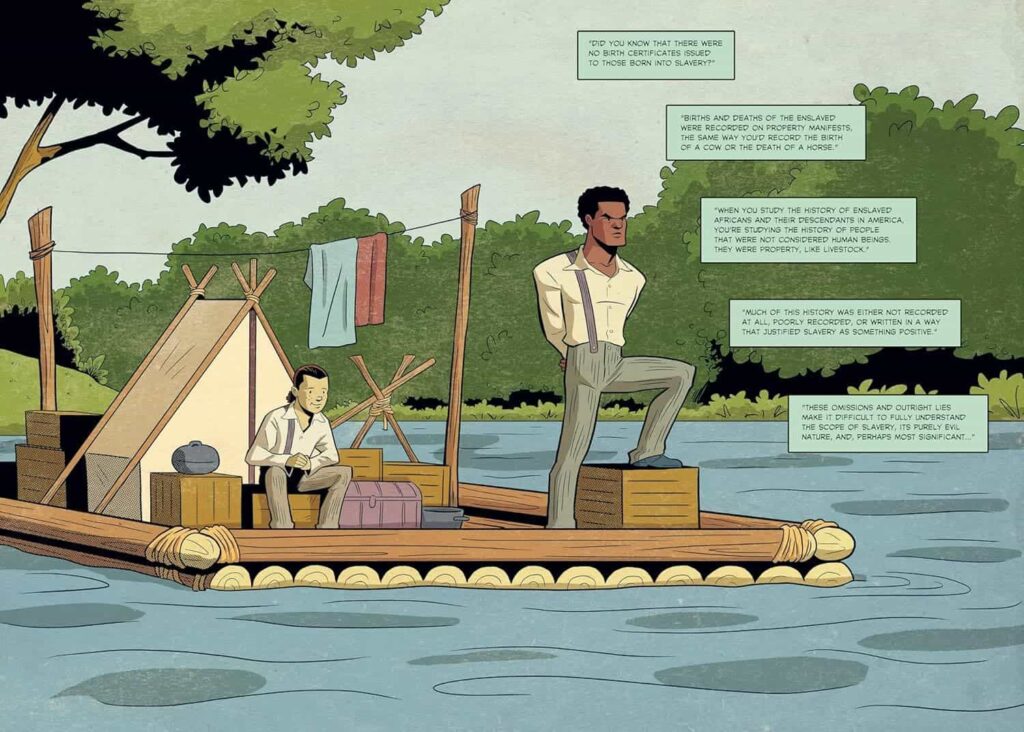

Jim is no longer the passive companion. He’s a man in pursuit of freedom, carrying the weight of what he’s lost and what he risks. Walker threads Jim’s story through the American Civil War, the trauma of slavery, and the volatile border conflicts of Missouri and Kansas. These layers don’t just enrich the plot—they illuminate the systemic forces shaping Jim’s life.

Big Jim and the White Boy doesn’t shy away from complexity. It embraces it, asking readers to sit with discomfort, listen, and learn.

Visual Storytelling That Speaks Without Words

Marcus Kwame Anderson’s illustrations are the soul of this graphic novel. His cartoon-inspired style brings warmth and immediacy to a story steeped in pain and resilience. Every panel is emotionally charged—grimaces, glances, and gestures speak volumes.

Anderson’s art doesn’t just support the narrative; it expands it. His ability to convey emotion without dialogue invites readers into a shared experience. As Walker puts it, “You can cry for a cartoon character. That’s the power of this medium.”

Rewriting the Canon: The Responsibility of Revisionist Literature

Reimagining a literary classic is no small task. Walker approaches it with reverence and resolve. He doesn’t erase Twain’s legacy—he interrogates it. Where Twain left gaps, Walker fills them with truth, empathy, and historical clarity.

Big Jim and the White Boy builds on the skeleton of Huckleberry Finn, adding to it. It’s a modern reckoning with a problematic artifact, offering a vision of justice and representation that Twain could not have.

Why Big Jim and the White Boy Matters Now

This isn’t just a graphic novel—it’s a cultural intervention. Big Jim and the White Boy invites readers to reexamine the stories they’ve inherited and the voices those stories have excluded. Walker and Anderson don’t diminish Twain’s work; they elevate it, ensuring Jim is no longer voiceless on a river of outdated narratives.

In reclaiming Jim’s story, they’ve created something timeless. Something that challenges, heals, and inspires. Big Jim and the White Boy reminds us that literature isn’t static—it’s a living, breathing force that can evolve toward truth.

If you want to add Big Jim and the White Boy to your own book collection, you can find it here (affiliate link).